“This sudden attention took me by surprise. One day I was considered an artist exploring highly personal combinations of form and content, and the next day I was calmly informed that I was a surrealist!” says Eileen Agar.

With its latest exhibition on surrealism, the Centre Pompidou invites visitors to an unprecedented deep dive into he movement born in 1924 with the publication of André Breton’s Manifesto. This maze of artworks, where art, literature, and cinema intertwine, offers an ambitious re-reading of this iconic period in art history.

This exhibition echoes a previous one, Surrealism au Féminin?, which focused on female creators who actively participated in the movement. Organized with a only female artists approach, it aimed at highlighting these often-forgotten creators to shed light on their essential contributions. This new exhibition raises the question: What changes have we observed in terms of gender representation in artistic exhibitions? Has the treatment of women artists improved since that retrospective, particularly in an era where social and ethical issues are central to contemporary debates?

With nearly 500 works and documents, the exhibition offers a rich thematic journey alternating between paintings, graphic arts, and the many extensions of surrealism, such as cinema and literature. True to the tradition of historical exhibitions, it aims to dazzle visitors while immersing them within the surrealist imagination.

AN AMBITIOUS EXHIBITION: LAYOUT AND THEMES

Overall Description

The exhibition is structured around 13 major themes, each divided into sub-themes spread across several rooms. It begins in narrow, dimly lit spaces that gradually open into larger, brighter rooms. The layout, designed like a labyrinth, genuinely evokes this sensation. Visitors move around a circular room, reminiscent of the spiral of a snail’s shell, which expands as one progresses.

The themes aim at synthesizing the many facets of surrealism. Among them are: Mediums, Dreams, Alice in Wonderland, Chimeras, Political Monsters, Mothers, Melusine, The Forest, The Philosopher’s Stone, Night, Eroticism, and The Cosmos.

This thematic approach seeks to cover the richness and diversity of surrealism while providing an overarching view.

Excessive Thoroughness?

The exhibition is extremely dense and it takes a long time to cover it. The first rooms, narrow and crowded with artworks, complicate navigation, particularly for visitors with physical disabilities. Guests must weave between paintings and installations, often at the expense of a smooth and comfortable experience. Adding to this challenge is the lack of seating, which prevents visitors from resting or fully immersing themselves in a piece, despite the lengthy nature of the visit.

While offering great variety and catering to diverse tastes, the abundance of works ultimately detracts from the experience. Too many paintings hung together overwhelm the visual space and hinder movement. Crowds gather, struggling to find their way or to contemplate the artworks under proper conditions.

It is only in the second half of the exhibition that visitors can access more spacious areas and finally breathe. However, by then, physical and visual fatigue may have set in:

- Visual abundance makes it difficult to focus on some specific artwork. This is compounded by the presence of large screens, particularly in the second room of the exhibition, which can be challenging for people who are photosensitive.

- The lack of seating throughout the journey forces visitors to remain on their feet, an added strain in such a long exhibition, especially for those with disabilities.

This lack of comfort ultimately weighs on the overall experience. While the intention to represent the diversity of surrealism is commendable, a more selective curation of works could have created a smoother, more enjoyable, immersive experience.

CREATING CONTRASTING ATMOSPHERES

Colors and Aesthetics of the Exhibition

The exhibition unfolds primarily in shades of gray and black, gradually transitioning to increasingly lighter shades of gray. This choice enhances the convoluted feel of the layout: visitors are never entirely sure where they are or whether they are leaving one gallery or entering a new one. This intentional disorientation seems designed to offer an immersive experience that mirrors the surrealist ethos of confusion, with artworks displayed on uniform and seemingly endless walls.

However, a few rooms stand out with splashes of color:

- A pale yellow wall in the section dedicated to The Realm of Mothers,

- Red walls in the section The Tears of Eros,

- A dark blue wall marking the transition to Cosmos.

While these variations provide some visual relief and create rhythm in the journey, the progression toward brighter lighting as the exhibition continues can strain the eyes. At times, the contrast between atmospheres lacks coherence and could be softened to enhance visitor comfort.

Visitor Comfort and Interactive Features

The exhibition aims to be accessible to a broad audience but struggles to fully achieve this goal:

- Physical access: As mentioned previously, the narrow spaces and overabundance of artworks make the layout less suitable for individuals with disabilities

- Comprehension access: For novices, the exhibition provides an overview of the main ideas of surrealism, serving as a kind of educational introduction. For more informed visitors, it functions more as a synthesis, with the diversity of artists displayed becoming the main attraction.

However, children and families are not well accounted for. The long journey and lack of playful interactions make the exhibition less engaging for younger audiences. A child-friendly path, at eye level or including interactive activities, would have been a significant asset, similar to the successful initiatives seen at the Musée d’Orsay.

Visitors are presented with a display that, despite its abundance of artworks, feels more like an open catalog than an immersive, contextual exhibition. As a complex and provocative movement, Surrealism, benefits from being explored through engaging methods such as projections, videos, or multisensory spaces.

Some interactive elements do appear in parts of the exhibition, such as well-chosen film excerpts like Hitchcock’s Spellbound, but these are sparse.

THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN SURREALISM AND IN THE EXHIBITION

Female Figures and Their Marginalization in Art History

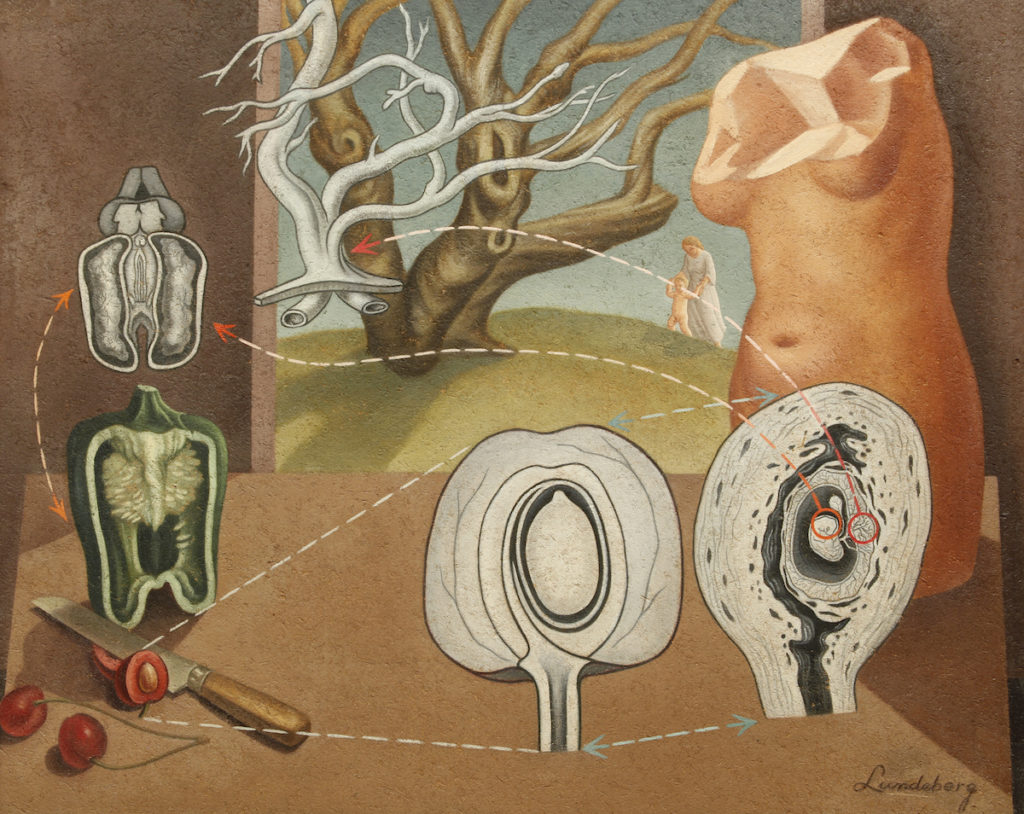

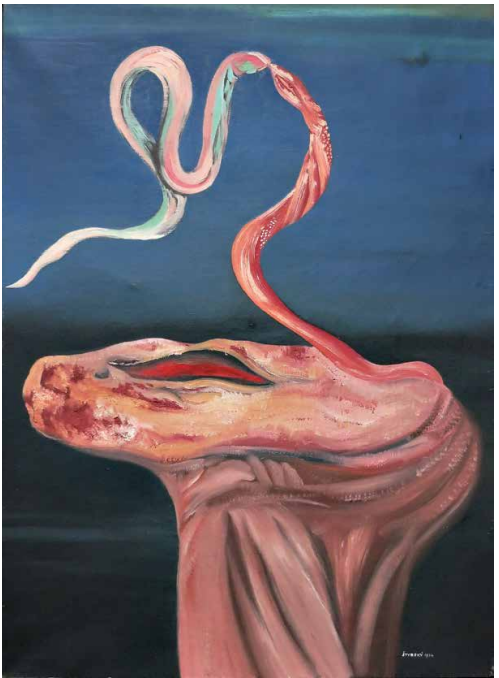

In this regard, the exhibition stands out positively: the inclusion of women is fully realized. Unlike many exhibitions where women are relegated to the status of “exceptions,” with only a few artworks on display, here they represent nearly 50% of the featured artists. They are not isolated in a dedicated section but are fully integrated into each theme. This approach presents them as active participants in surrealism rather than as marginal or accessory figures. This progress appears to stem partly from the work initiated in the exhibition Surréalisme au Féminin ?, which had already started redefining their place in the movement’s history. Some works featured in that earlier exhibition reappear here, but the current selection stands out by presenting new pieces and deepening our understanding of women’s contributions. Their themes, techniques, and compositional choices significantly enrich our perception of surrealism.

For example, Suzanne Van Damme’s Couple d’oiseaux anthropomorphes (1944) offers a unique perspective. This work subtly questions the relationship between gender and representation, a theme often overlooked by male surrealist artists. By attributing human behaviors and attitudes to birds, Van Damme highlights gender biases imposed on both sexes, while criticising the dynamics of power they generate. This poetic yet critical dialogue about stereotypes and gendered categories considerably enriches our understanding of surrealism.

Female Creators in the Exhibition

Among the celebrated female artists, we find iconic figures such as:

- Leonora Carrington, Dora Maar, Remedios Varo, Claude Cahun, Meret Oppenheim, Toyen,

- And many others, showcasing the diversity of women’s contributions to the movement.

Their equal treatment with male artists is a true success. They are highlighted not as curiosities or muses but as creators in their own right. This recognition resonates with the audience: throughout the exhibition, one can hear visitors marveling at their works, enthusiastically commenting on them, and sometimes expressing greater admiration for them than for their male counterparts.

Certain works deserve to be spotlighted as powerful examples of their contribution to surrealism, such as:

Although the exhibition also includes texts and writings by some female creators, it lacks a more in-depth reflection on their impact on the artworld. How did they contribute to writing surrealism’s history or questioning its codes, and how does this enrich our understanding of the movement?

Room for Further Exploration?

While the exhibition succeeds in showcasing female creators, it is more reserved in exploring representations of gender.

- For instance, in the Melusine section, female representations lack contextualization. Who is Melusine? What symbols are associated with this figure in the artists’ works?

- Similarly, in The Tears of Eros, representations of sex and women are approached aesthetically but lack deeper analysis regarding gendered meanings or dynamics of power.

Surrealism has always played with notions of gender, deconstructing and reinventing them, but the exhibition only partially delves into this theme. Clearer educational frameworks could have gone beyond visual contemplation to explore central surrealist concepts, such as:

- The reinvention of traditional roles through mythological figures like Melusine.

- The interplay between masculine and feminine in the works of Claude Cahun or Toyen.

- How female creators used their works to respond to or subvert dominant male visions within the movement.

This raises the question of whether surrealism is as equalitarian as this exhibition might suggest. However, it avoids addressing the misogynist aspect of the movement or from certain members within it.

Lastly, a feminist perspective through history on women’s contributions to surrealism would have added an essential layer of analysis to understand their place—not only in this movement but also in an ever-evolving history of art.

BETWEEN DISCOVERY AND FRUSTRATION: THE TRANSMISSION OF KNOWLEDGE

Uneven Educational Content

For knowledgeable enthusiasts of surrealism, the exhibition’s explanatory panels offer little new information. They remain very general, merely introducing the main concepts and themes of the movement. While this approach may suit a novice audience, it risks leaving visitors seeking deeper insights or fresh perspectives somewhat unsatisfied.

The decision to favor an introductory approach is likely due to the exhibition’s length, but this choice quickly reveals its limitations. The abundance of artworks, visual stimuli, and themes overwhelms the visitor’s attention. In such a context, it becomes difficult to linger over the explanatory panels, which often go unnoticed:

- Panels placed in narrow spaces cause crowds to gather, blocking navigation.

- This has a deterrent effect, preventing visitors from reading the texts comfortably.

The labels accompanying the artworks, although present, suffer from several major flaws:

- Size and readability: They are often too small and placed too low, making reading complicated, especially in crowded spaces.

- Lack of detail: The information provided is minimal, failing to place the artwork in a broader context or allowing visitors to fully appreciate its contribution to the theme.

For an exhibition of this scale, an additional effort to enhance the quality of the educational materials would have been welcomed.

CONCLUSION

The surrealist exhibition at the Centre Pompidou amazed with the scale of its ambition: 500 works spanning a century of creation, exploring diverse regions such as Latin America, Japan, and the United States. However, this abundance of works and themes, while enriching, tends to scatter the visitor’s centre of focus rather than articulating a clear narrative. While the major names—Dalí, Magritte, and Max Ernst—provide solid anchors, works by lesser-known creators struggle to find their place in this sprawling collection, often presented without the necessary context to fully grasp their significance.

The exhibition occasionally strays from the central history of the movement by attempting to cover too much, including late works from the 1960s and international extensions. This might irritate those seeking a clear and concise overview, especially compared to previous exhibitions such as La Révolution surréaliste (2002) at the Centre Pompidou or Surréalisme au Féminin? (2023) at the Montmartre Museum, which stood out for their clarity and focus. Here, although the immersive and thematic approach is appealing, it loses coherence for quantity.

Nonetheless, the exhibition captivates with its diversity and the special attention given to female creators, who are often overlooked this movement. Its notable success in drawing crowds, even on weekdays, hints at the potential for it to become a “blockbuster” exhibition in the sense of Emma Barker (Contemporary Cultures of Display), should it reach 250,000 visitors. Already travelling, the exhibition began in Brussels and will move to Madrid, Hamburg, and Philadelphia by 2025, offering an international audience the opportunity to explore this retrospective.

In the end, this exhibition highlights the ongoing challenge of balancing ambition and access. It is a commendable attempt that, with greater concision, could have left a more lasting impression.

Written by Ariane TASSIN