Mostly remembered sitting for John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1851), Elizabeth Siddal kicked off interest in women artists of the Pre-Raphaelite movement

Watercolour on paper, 13.7 x 13.7 cm, Tate Britain, London

Life’s work

“Art was the only thing for which she felt very seriously” wrote Dante Gabriel Rossetti to poet Algernon Swinburne about his deceased wife. Elizabeth Siddal’s brief but nonetheless spectacular biography reads likes sensation fiction. Pictures of her evoke a certain type of beauty, characterised by pale complexion, heavy-lidded eyes and abundant red hair. Indeed, she became the first Pre-Raphaelite “stunner” by crafting the iconic look of the fair medieval maiden: www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millais-ophelia-n01506. Remembered through visual and textual depictions, the conflation of her image as a tragic muse has overshadowed her creative output.

However, she was already acknowledged as “a real artist” by peers during her lifetime. While Rossetti promoted her “power of designing (and) fecundity of invention”; her patron John Ruskin ranked her amongst “geniuses” like Turner. Despite few years of practice, she crafted a significant body of work: nowadays, a hundred or so paintings, drawings and sketches are spread across various British and American collections, public or private. Apparently not meant to be published, about fifteen poems and fragments have been recovered: www.victoriansecrets.co.uk/book/my-ladys-soul-the-poems-of-elizabeth-eleanor-siddall/. Many of these pieces have survived in the form of photographic portfolios compiled by Siddal’s husband after her death. These are visible, by request only, in the Ashmolean and Fitzwilliam Museums’ print rooms (Oxford and Cambridge).

Curbed by Rossetti’s studio and the annual allowance of £150 he secured on Ruskin’s behalf, she was denied classical artistic education, restrained to a narrow range of techniques and from commercial transactions. Historical and critical interest in Siddal’s career has then dismissed her achievements as limited or due to her addiction to laudanum. Only recently have curators and scholars taken more serious heed of her pictorial and poetical production.

Exhibition history

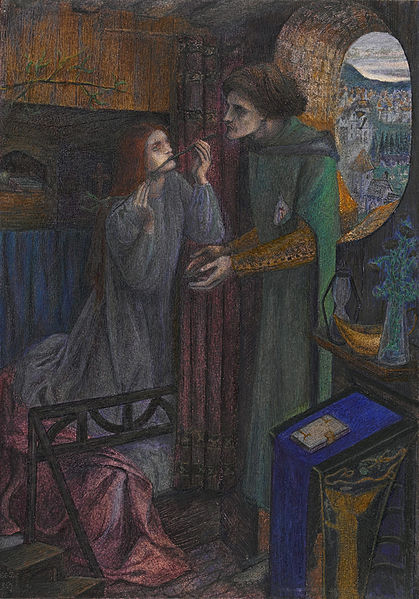

Clerk Saunders, 1854

Pencil on paper, 8.9 x 14 cm

Private collection

1854-7, watercolour with arabic

gum on paper

25.4 x 19.1 cm

Denis Lanigan collection

1857, watercolour and

chalks on paper

28.4 x 18.1 cm

Fitzwilliam Museum

Through the lens of feminist intervertions in the field of art history, Siddal’s career have been reassessed: she was included in the inaugural travelling exhibition on female painters curated by Linda Nochlin and Ann Sutherland Harris, from L.A.’s County Museum to the Carnegie and Brooklyn Museums (1971). It notably displayed her illustration of the ballad Clerk Saunders. At this stage, Elizabeth Siddal’s birthdate was incorrectly believed to be around 1834. It seems that both herself and those who mentioned her fancied her as younger. As archivist of the family heritage, her brother-in-law William Michael Rossetti provided the chief basis on available information repeated in numerous writings.

As in the 1857 show of Russell Place nearby her colleagues, Elizabeth Siddal was the sole woman to feature in the Pre-Raphaelite exhibition held at Tate Gallery in 1984. Two other watercolours, The Holy Grail and Lady Clare, were presented. Her entry in the catalogue was the first attempt to disentangle Siddal’s practice from perpetual comparisons with Rossetti’s. By introducing Siddal as a cipher of gender difference, Deborah Cherry and Griselda Pollock challenged concepts of genius and originality coined in masculine terms.

Watercolour on paper, 28 x 23.8 cm, private collection

One of the other lead researchers to document Elizabeth Siddal was Jan Marsh. She was involved in all the leading exhibitions showcasing the artist during the last decades. The 1991 retrospective at the Ruskin Gallery sought to register the whole spectrum of her production. Just as astute was the 2018 monographic display of Wightwick Manor, exposing its own Siddal collection bought at auction by the Manders couple in 1961: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/wightwick-manor-and-gardens/features/a-celebration-of-lizzie-siddal-artist-and-poet.

The major contribution of Jan Marsh in the revision of Siddal’s biography was about her entry into the artworld. It was in 1894, through Frederick George Stephens, that the story of her discovery in a bonnet shop by fellow painter Walter Deverell surfaced. Nevertheless, a Sheffield obituary had stated that thanks to her trade, she became acquainted with Deverell’s father, Secretary of the London School of Design, to whom she showed sketches. Even though The Lady of Shalott is her first work dated and signed (E.E.S. 15 Dec. 1853, see header), this implies that she was drawing before she started studying under Rossetti’s tuition.

the sister arts

Because her verse has been understood as the result of personal expression, Siddal’s pictorial and poetical production have been examined as disjoined modes of creation. However, she was engaged in a total form of art, through which text and image echoed each other. The groundwork of her pictures is illustration of stories that appealed to her, conveying a strong sense of narrative. An equivalent process is to be found in her lyrical rhymes.

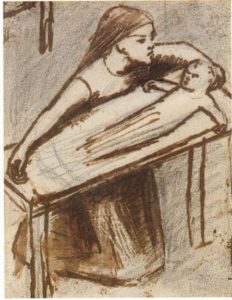

Neglecting the staple motifs captivating the Victorians – Greco-Roman mythology – she favoured religious subject-matter, local folklore and British literature. Moral subjects drawn from the Bible permitted her to reconfigure the traditional Virgin and Child theme in a disquieting transcription of motherhood. The emotional charge of her Nativity series translates in the proximity between Christ and Mary.

Nativity, c.1854

Pen and ink on paper, 12.5 x 22 cm

Peter Nahum collection

Nativity, c.1860

Graphite on paper

19 x 18.5 cm

Wightwick Manor, Wolverhampton

Madona and Child, c.1852

Watercolour on paper, 17.9 x 9.7 cm Ashmolean Museum

Popular beliefs and macabre legends were a great influence too. Clerk Saunders represents an old Scottish ballad. Here, May Margaret meets with the ghost of her lover previously killed by Margaret’s brothers. As Clerk Saunders appears through the wall, Margaret makes a vow of loyalty by kissing the wand she’s about to give him. Similarly, fantastic beings and doomed couples were recurrent figures in her poems: “Farewell Earl Richard/ Tender and brave/ Kneeling I kiss/ The dust from your grave”.

poetical language

Elizabeth Siddal enjoyed dramatising literary classics, such as Shakespeare’s Macbeth, but her main taste lied in Romantic and contemporary poetry. Keats, Tennyson and Browning and ranked amongst her most frequent sources of inspiration. However her re-adaptation of Tennyson’s “Lady of Shalott” demonstrates an impression of quietness, as if the main protagonist is controlling her fate as she observes Knight Lancelot through the window. Contrary to other Pre-Raphaelite versions, the Lady doesn’t appear as an alluring fallen woman whose redemption will be achieved through death. Sharing a penchant for the Arthurian Cycle with her fellow artists, Elizabeth Siddal directed her attention to contemplative figures rather than heroic deeds of action.

Pen, brush and Indian ink on paper with scratching out, 21,4 x 13.5 cm, Ashmolean Museum

Variation and repetition are at the core of Siddal’s sense of composition. It allowed her to propose another take on the initial text. Her economy of means materialises in the use of the same sheet to draw diverse set of studies. In writing, slight modifications of a line from one stanza to the next generate a melody that sounds like nursery rhymes: “O mother open the window wide (…) And mother dear take my young son (…) And mother, wash my pale hands”. Simple and unsophisticated, Siddal’s works privilege intensity of feeling and thruthfulness. Love, death, the passing of time and nature are the leitmotiv of her art that resonates with Gothic tones.

Mainly operating on paper, Siddal treated all the elements of the composition with similar depth. She rejected strict notions of perspective and organisation into grounds to enclose her characters in a narrow space. Usually avoiding chiaroscuro, she regarded her pictures like medieval illuminated manuscripts by trying to make tints more opaque through the use of bodycolour, which heightened contrasts. When she wanted to suggest balance in light and shading, she employed brown or sepia ink (sometimes enhanced with charcoal and chalks), as shown in her Macbeths’ study. These reveal her distinctive style of figure drawing as well, defined by linear shapes. Likewise, Siddal’s poetic language pinpoints the reader’s attention to colour and form.

O silent wood, I enter thee/ With a heart so full of misery/ For all the voices from the trees/ and the ferns that cling about my knees

In thy darkest shadow let me sit/ When the grey owls about me flit/ There I will ask of the a boon/ That I may not faint or die or swoon

Aware of Victorian artistic traditions, Elizabeth Siddal exploited the potentials of Pre-Raphaelitism that bound her to the archetype of the accomplished yet vulnerable lady, but it also enabled her to find her authorial voice as painter and writer. Still a powerful icon in the collective unconscious, away from contemporary standards of femininity, the mystery shrouding the figure of Elizabeth Siddal resists any bid of definite scrutiny. If we wish to broaden our conception of British cultural heritage (non-binary, all-inclusive), she certainly deserves to be a part of it as an active creator in her own right.