A founding member of the Impressionists and the only woman to join in their first exhibition, Berthe Morisot attempted to seize slices of modern life with swift brushstrokes and pastel-hued tones

Self-portrait, 1885

Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm

Musée Marmottan-Monet

“They’ll become painters”

Berthe Morisot was born in an affluent family with a fondness for the arts. She grew up in chic Western Paris. Her father was a senior administrator who had studied architecture at the School of Fine Arts. Her mother was, supposedly, the great-niece of Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

As befits a bourgeois environment, Berthe Morisot, along with her sisters Yves and Edma, took music lessons. They started to study art from 1857 with Alphonse Chocarne, who taught them the basics of drawing. The sisters had little affinities with Chocarne. Yves soon gave up painting. Berthe and Edma decided to enter the workshop of Joseph Guichard, who enabled them to copy masterpieces from the Louvre : classical statues and Italian Renaissance painters such as Titian and Veronese. “They’ll become painters” asserted Guichard to the sisters’ parents.

Oil on canvas, 60 x 73.4 cm, private collection

Through Guichard, the Morisot sisters met landscape artist Camille Corot and other members of the Barbizon school. Berthe was expressing a growing interest for plein-air painting, often working in watercolour. In 1864, the Morisot sisters made their Salon débuts as amateur painters. The first review of a painting by Berthe was released in the press: “the white fabrics wrapping the young lady’s body are so fine and lavishly coloured, the landscape’s hues are real (…) painted with much energy”. Edmé Tiburce Morisot set up a workshop in the garden’s house for his daughters, while their mother welcomed Parisian fashionable society (politicians, artists, writers) on Tuesday evenings.

Relationship status: it’s complicated

In the end of 1867, during a sketching session in the Louvre, the Morisot sisters got acquainted with Édouard Manet thanks to painter Henri Fantin-Latour. After the scandals related to Lunch on Grass and Olympia (1863), Manet had made for himself quite a reputation. In the first place, Edma Morisot communicated her fascination to the painter, but her wedding to a naval officer made her quit art practice.

Edouard Manet, The Balcony, 1862 Oil on canvas, 170 x 124 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Berthe Morisot, Woman and Child on a Balcony, 1872, oil on canvas

61 x 50 cm, Ittleson Foundation

Manet, Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, 1872

Oil on canvas, 55 x 40 cm

Musée d’Orsay

The close link building up between Berthe Morisot and Édouard Manet at that time was rather complex. The possibility of a sentimental relationship between the two artists may have been exaggerated by biographers. Morisot sat for the Edouard Manet a dozen times, but contrary to his other model, Eva Gonzales, she has never been portrayed as an artist at work, but rather as a “femme fatale”, as critics pointed out. Besides, Manet required her to make alterations to her canvasses (Young Lady by the Window, 1869) or even re-painted some parts (Mrs Morisot and her Daughter, Mrs Pontillon, 1870).

And yet there was a fruitful, mutual exchange in their practice. Manet took up Morisot’s motif of the figure seen from the back from Woman and Child at the Balcony for his Railway of 1872-1873. The railings of this canvas by Morisot hark back at The Balcony by Manet. She sometimes resented this influence: “I’ve realised it looks just like Manet” she wrote to her sister about this View of Paris, “I am quite upset about it”.

Oil on canvas, 46 x 81.6 cm, Santa Barbara Museum of Art

In 1872, Morisot asked Manet to show her work to art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who bought some of her canvasses and watercolours. Her colour range became lighter, less inspired by Manet’s style. The stays at her sister’s second home in the outskirts of Paris show this evolution (The Cradle ; The Butterflies’ Hunt, 1874).

The same year, Morisot got married to Edouard Manet’s brother, Eugene. She never sat for Manet again, but did her utmost, after the painter’s death in 1883, to acquire the portraits he had made of her. She organised a monographic exhibition in 1884 dedicated to him, and joined forces with Claude Monet to make the State purchase Olympia.

First impressions

December 1873: Berthe Morisot, as well as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Auguste Renoir et Edgar Degas founded the Anonymous, Cooperative Association of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers. Manet was invited, but refused to join. Even if Morisot’s painting, Blanche, had been accepted, the Salon jury of 1873 had been particularly harsh. This alternative society would enable its participants to exhibit outside of traditional institutions.

The first Impressionist exhibition took place in 1874. One week before the opening, painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes had tried to deter Morisot from participating, but there she displayed fourteen oils on canvasses (including The Cradle), three pastels and three watercolours.

Oil on canvas, 56 x 46 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The following year, Morisot and the Impressionist group were involved in an auction sale at Drouot’s. This created such an uproar that policemen were placed in front of the building. According to Renoir, Pissarro punched someone in the face for calling Morisot names because she dared to sell her work. She achieved the highest price with Young Woman with a Mirror (480 francs).

Albert Wolff ranked amongst the most scathing reviewers of Impressionism, but at the second show of 1876, he singled out Morisot’s paintings as more palatable to the eye: “there’s also a woman in the lot – such is the case in any famous groupings – her name is Berthe and she looks rather strange. Her feminine grace remains stable within the excesses of delirious spirits.”

60.3 x 80.4 cm, Art Institute of Chicago

From 1877 onwards, Morisot’s “uncomplete” touch, for which she had been reprimanded, was seen in a more positive light. Critics started to praise her feathery brushstrokes and carefully-orchestrated compositions. Woman at her Toilette met with general acclaim at the fifth Impressionist exhibition. For George Rivière, Morisot had even managed to outshine her master: “Her eye (…) is even more sensitive than Mr Manet’s”.

a family of one’s own

Aboard a Yatch, 1875

Watercolour on paper, 20.7 x 26.8 cm

The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown

English Seascape, 1875

Oil on canvas, 43.8 x 64.8 cm

Newark Museum

The 1870s were punctuated by her wedding and the birth of her daughter. In 1875, the Manet couple spent their honeymoon in England, where Berthe Morisot could admire the works of Gainsborough and Turner. The seascapes she made in watercolour conveyed the shimmering water reflections and whimsical weather effects of the British coasts. The canvas on the right depicts the buoyant activity of Cowes, a seaport town located in the Isle of Wight.

Morisot’s husband remained a constant support throughout her career. Interestingly, Eugène Manet is the only grown-up man featuring in her oeuvre. In this painting made during the couple’s English holiday, she replaced the traditional female figure circumscribed to an interior with a portrait of her husband’s. He is seating with almost his back to the viewer, facing the window. This interplay of gazes, inside and outside spaces, is characteristic of Morisot’s elaborate compositions.

38 x 46 cm, Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris

Morisot had become “Mrs Manet” for her friends, but she kept signing her work with her maiden name. Her fame and social status led her to receive celebrities from the artworld on Thursday evenings. She seemed to dislike Eva Gonzalès, but befriended other women revolving around the Impressionists, such as Marie Bracquemond and Mary Cassatt. Thanks to the American artist, she was involved in two exhibitions of the Woman’s Art Club of New York. Morisot was particularly close to poet Stephane Mallarmé, who became her daughter’s guardian when Eugene Manet died in 1892.

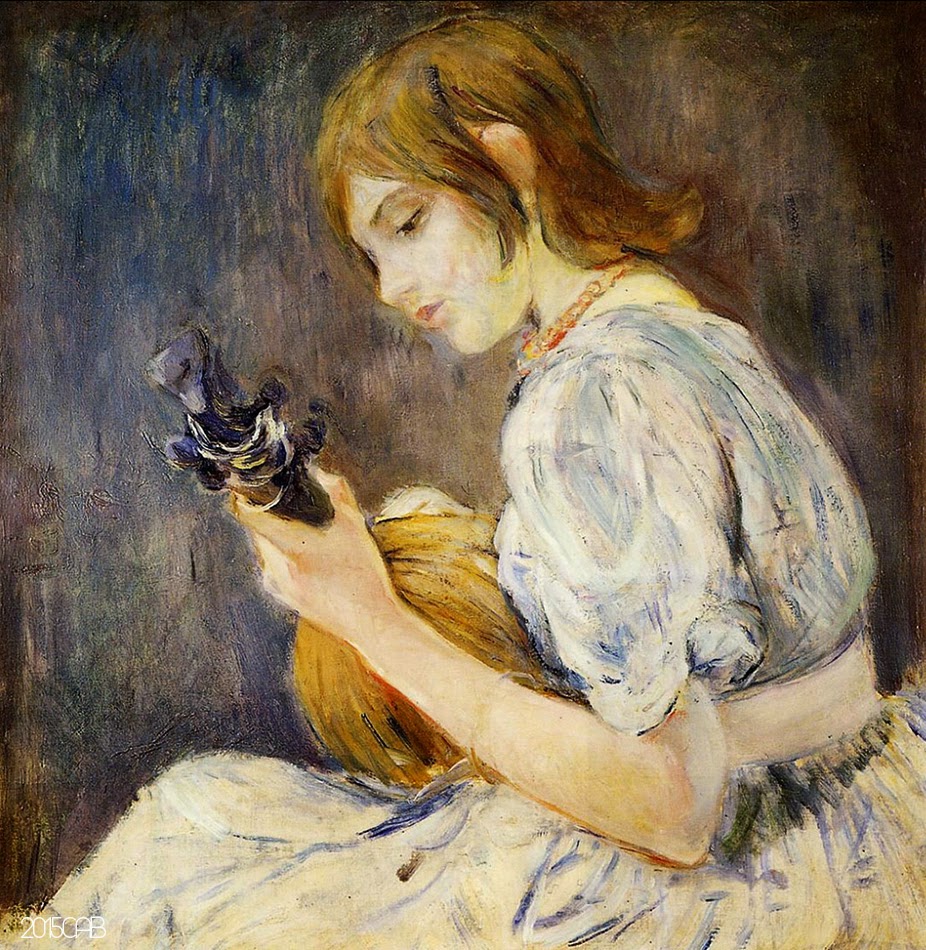

The birth of Julie Manet was the only event that could make her miss an Impressionist exhibition. Julie Manet soon became her favourite model, portrayed in an endless array of poses and activities. These canvasses show the child growing up and the passing of time. Mother and daughter shared everything, notably art practice.

Sandcastle, 1882

Oil on canvas, 92 x 73 cm

Private collection

The Mandolin, 1889

Oil on canvas, 55 x 57 cm

Private collection

Julie Daydreaming, 1894

Oil on canvas, 64 x 54 cm

Private collection

Shine a light

Berthe Morisot had thus become a leading figure of the Impressionist movement. In 1882, she was exhibited in London, and showed some pieces alongside Pissarro and Monet at two Salons of “the XX”, an avant-garde group of Belgian painters, sculptors and engravers. Thanks to Durand-Ruel, her work was displayed at the New York National Academy of Design in 1886 and at other institutions in the United States. This enabled her to get better acquainted with the American art market.

Her first solo exhibition took place in 1892 at the Boussod and Valadon gallery founded by Adolphe Goupil, an art dealer formerly opposed to Impressionism. This event was much celebrated in the press. Furthermore, when Gustave Caillebotte died in 1894 and bequathed his collection to the French State, Mallarmé pointed out the absence of Morisot’s work. Following his advice, the Museum of Living Artists (actual Musée du Luxembourg) purchased Young Girl in a Ball-Gown.

Oil on canvas, 71 x 54 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

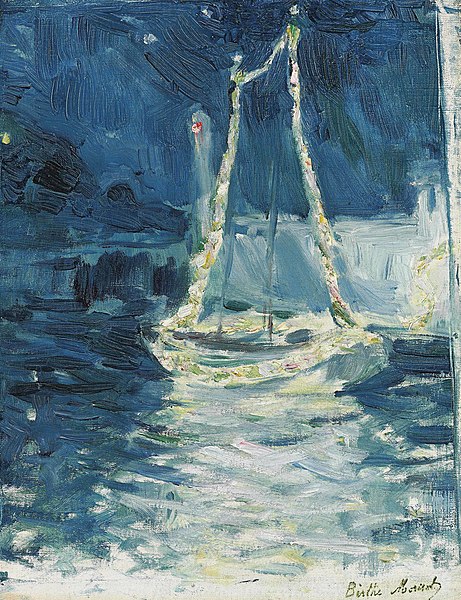

In the 1880s, Berthe Morisot spent almost every winter in Nice. She enjoyed the South for its warm weather and dazzling light. She often sailed on fishermen’s boats to paint directly from the motif. Illuminated Boat was made during her last stay in Nice. It displays the glittering reflections of the moon onto the ripples.

Villa with Orange-Trees, 1882

Oil on canvas, private collection

The Port of Nice, 1882

Oil on canvas, 43 x 53 cm

Musée Marmottan-Monet

Illuminated Boat, 1889

Oil on canvas, 26.4 x 20.5 cm

Private collection

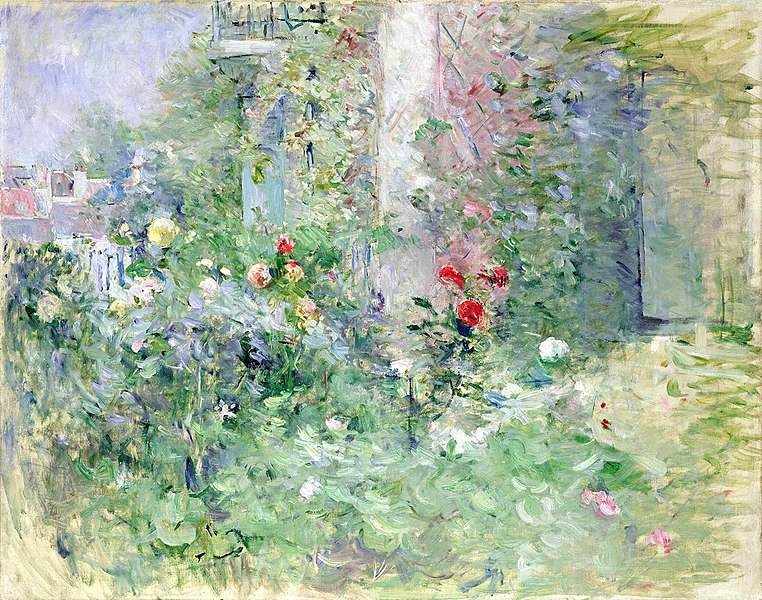

Morisot’s interest in landscape can also be perceived in the many images of her secondary residence located in the South-West suburbia of Paris. Her style, which grew more and more dynamic, makes us feel that paint has been applied in a single session. Compositional devices are quickly delineated, and colours patches seem to appear in a blur. But light, and light especially, catches the viewer’s eye.

Oil on canvas, 73 x 92 cm

Musée Marmottan-Monet

Innovating

Berthe Morisot tried to recreate movement in her canvasses. She was inspired by her surroundings, the natural environment, and daily life. Modernity in 19th century art has traditionnally been defined according to the terms of Charles Baudelaire. ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ explores the interrelations between aesthetics and lifestyle within the scope of the public domain, dominated by the male gaze.

However, Morisot’s subject-matter was inherently contemporary. She didn’t hesitate to depict domestic toil. By relentlessly representing laundrywomen, seamstresses and wet nurses, she endowed these silent, unvisible activities with dignity.

Oil on canvas, 46 x 67 cm

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Morisot’s way of experimenting with expressive brushstrokes reveal her constant research on oils’ material aspect. She sometimes scraped her canvasses to achieve various textures, while some were completely covered with paint. From 1885, she gave more significance to outline. This emphasis on simplified shapes betrayed an influence of Japanese prints, by placing compositional elements away from the centre. Sitters were easily recognisable, but her technique bordered onto abstraction.

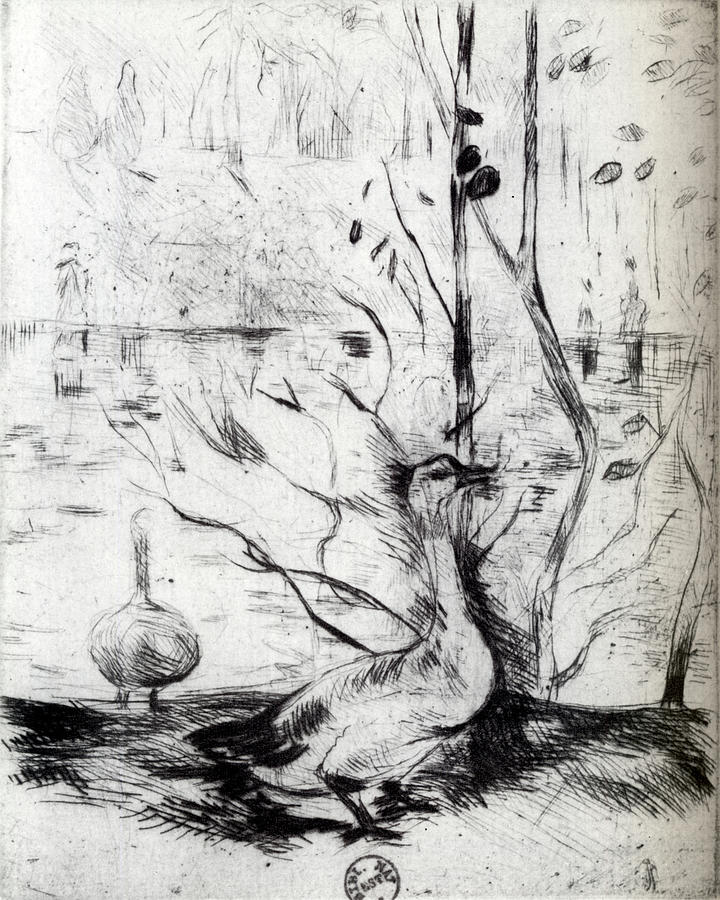

In her final years, Morisot explored other artistic media, ranging from sculpture to etching. She illustrated a collection of poems by her friend Mallarmé. Her Cherry-Tree series is a double portrait of Julie and her cousin, Jeanne Gobillard, in the Manet house-garden. She came up with these monumental compositions after many charcoal and pastel sketches.

14 x 11 cm, Musée Marmottan-Monet

legacy

84 x 154 cm, Musée Marmottan-Monet

Berthe Morisot died aged 54, after caring for her daughter who had been sick. She donated most of her artworks to her Impressionist friends. The first posthumous tribute was a retrospective show at the Durand-Ruel gallery in 1896. Mallarmé wrote the catalogue’s introduction.

Julie Manet described the excitement caused by this event in her diary: “at the end of the day, you wonder how we’ll ever be ready for tomorrow (…) as the sun sets, as a few paintings only retain some sense of light and as these portraits of young ladies seem even more lively, the Japanese screen really looks like a wall. Mr Monet has asked Mr Degas to remove this screen in the backroom, but Mr Degas argues that people won’t see the drawings anymore”.

Berthe Morisot has fared well in the lineup of European and American institutions: the Musée de l’Orangerie has dedicated a major exhibition to her in 1941 and in 1960 she was celebrated at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In the mid 80s, a travelling show was organised at the National Gallery of Washington, whose works went to two other American venues. More recently, the Thyssen Museum in Madrid (2012) and the National Museum of Fine Arts in Québec (2018) have set up monographic exhibitions.

Thanks to the bequests of the artist’s heirs, the Musée Marmottan-Monet owns the largest public collection of Morisot’s works: www.marmottan.fr/en/collections/berthe-morisot/. In 2013, Morisot became the best-priced woman artist when After Lunch (1881) was sold at a Christie’s auction for $10.9 million. The Metropolitan Museum (bit.ly/3bADydl) and the Art Institute of Chicago (bit.ly/3i8XDZo) boast a nice range of drawings accessible online. You can discover her paintings on display with our Musée d’Orsay tour: womensarttours.com/visite/danger-women-at-work/.

“I don’t think there’ll ever be a man treating a woman as an equal. This is the only thing I’d have required, because I know I’m worth it”

Berthe Morisot, 1891

2 replies on “Berthe Morisot (1841-1895)”

you are truly a just right webmaster The site loading speed is incredible It kind of feels that youre doing any distinctive trick In addition The contents are masterwork you have done a great activity in this matter

Thank you very much for this kind comment, but you have to be grateful to Christophe Leonardi for that! He did everything from top to bottom, with incredible insight and layout.