Born from models of equity and democratisation of culture, can the Louvre Museum still maintain its motto of universalism?

the eternal feminine

If you think of the Louvre, you’ll have no difficulties identifying its renowned icon, arguably the most famous painting in the world: that is, La Gioconda. Identified as Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a rich clothing merchant, the model’s still attract crowds desperate to take a selfie with her. Little is known about Mona Lisa the woman, her popular enigmatic stare and smile accounting for her mysterious history.

Leonardo Da Vinci

The Mona Lisa

1503-1519, oil on wooden panel

77 x 53 cm

Artemis with a doe, 2nd century A.D.

Marble, 200 cm

In the world’s biggest museum, the celebration of the female body is depicted in an endless array of poses and techniques. Goddesses, queens, saints, heroines, women of power or caught in their interiors: all embody emblems of a first-class collection. As unquestionable canons of beauty, they typify the eternal feminine offered to the pleasure of the viewer’s gaze. Across various time periods and locations, they define rules of representation of the human body. The Venus de Milo, Liberty Leading the People, Artemis with a Doe, and Winged Victory range among the other “big five” of the museum, always sought-out by visitors.

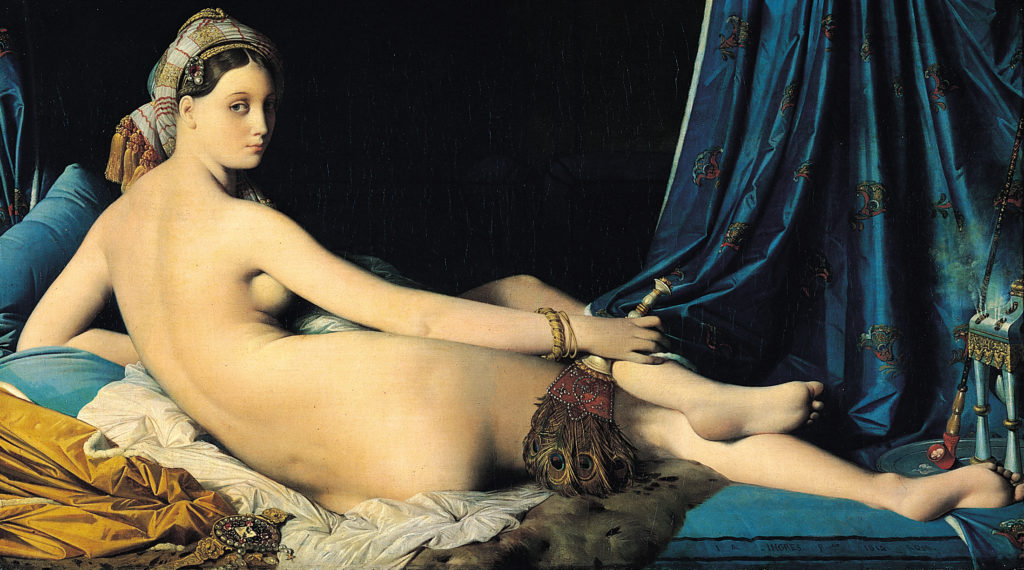

“Do women have to be naked to enter the museum?” used to claim activist group Guerilla Girls in the late 80s on billboards featuring Ingres’ supine nude in his Great Odalisque. It is said that the Louvre comprises a totality of 460 000 exhibits. Only 663 or so of these have been attributed to women artists. Which means that in large European and American museums, 5% to 10% of their collections is devoted to female creation. A rate that gives food for thought when one realises it equates the proportion of lady artists admitted to the Salon – the official exhibition of the Royal Academy held in the square room of the Louvre Palace lent by the King – before the French Revolution. Initially though, the Louvre as an encyclopedic museum was created to determine standards of excellence. Ordered through “schools” expressing the evolution of styles by Old Masters, its collection was meant to be diverse and representative of mankind’s progresses. When the Central Museum of the Arts opened in 1793, many painters already had their workshops in the former palace.

Oil on canvas, 91 x 162 cm

the woman-artist question

Oil on canvas, 88 x 73 cm

However, the Louvre does feature works by artists celebrated during their lifetime. Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744 – 1818, see header), Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749 – 1803) and Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755 – 1842) – the sole female painter of the Ancien Régime to have been the subject of a major retrospective in Paris recently (www.grandpalais.fr/en/event/elisabeth-louise-vigee-le-brun) – were labelled “The Three Graces” by their contemporaries, thanks to their skills. The Royal Academy of the Arts institution didn’t ban women entirely, but when it was founded in 1648, applications by women were so numerous that their entries were limited to a number of 4 for fear of competition. The only candidate to be received within the portraiture category, Sophie Chéron (1648– 1711) depicted herself looking directly at the viewer. Reception pieces were extremely codified exercises, but Chéron accomodated the jury by placing a drawing in her hands, the basis of academic training. This was a means to claim her status as a creative individual.

The quota was technically maintained until the visit of a foreign artist: Venetian-born Rosalba Carriera (1673-1757). She got extremely popular amongst the French nobility for whom she made around 30 pastel portraits, launching the craze for this medium. “La Rosalba” drew directly on paper without any preliminary sketches. The powdery aspect of pastel enabled her to render with subtelty the variations of skin-tones. Sent to the Academy in 1722 from Venice, The Nymph of Apollo was praised for its technical abilities.

Rosalba Carriera

Young girl with laurels, nymph of Apollo, 1721

Pastel on paper, 61.5 x 54,5 cm

Rosalba Carriera

Head of a young girl, 1703

Pastel on paper

36.2 x 30.2 cm

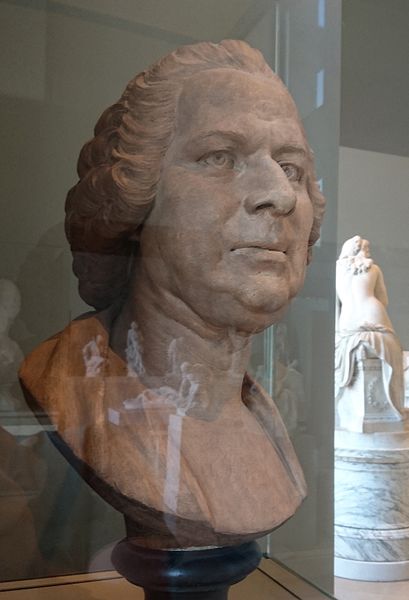

The 2nd half of the 18th century was beneficial to women wishing to enter the artworld. 1783 witnessed some unprecedented event in the Academy’s history: the simultaneous reception of two lady artists perceived as rivals in popular opinion. Already known thanks to her ties to painters settled near the Louvre where she grew up, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard had the reputation of some hardworker. Supported by the Countess d’Angiviller, the wife of Louis XV’ minister of the arts, and the Academy’s director, she was received thanks to her portrait of scultor Pajou, a friend of her father’s. Socialite Elizabeth Vigée-Lebrun was daughter of a pastel artist who noticed her gifts from a very young age. Technically, her husband’s profession – art dealer – prevented her entry: following the bill of 1776, the Academy forbade members to sell their work for their own account. But Vigée-Lebrun was protected by Queen Mary Antoinette who requested a special exemption from M. Lebrun’s activities.

With the waning of the Ancien Régime, the situation of successful women artists became precarious. The academic system was loosing its influence. Despite the the institution’s reluctance, Neo-Classical painter Jacques-Louis David opened his studio to ladies in 1786, paving the way for subsequent feminine sections in masters’ workshops. Still, the reputations of women renowned through their royal allegiances – such as Anne Vallayer-Coster or Vigée-Lebrun – was under jeopardy. Others, like Marguerite Gérard (1761-1837), managed without institutional support and decided to take advantage of the change of taste in patrons, producing small scenes of daily life.

Sculptor, 1783, 73.5 x 61.8 cm, pastel on paper

The French Revolution fostered many promises. Adélaïde Labille-Guiard sided with the reformist party, wishing to open the Academy to women without limitations. The Salon of 1791 was devoid of jury, leaving ample room for female candidates. However, David’s faction of abolitionists won in 1793 and the Academy was replaced by the Commune of the Arts. The question to admit women had not really been really spelled out, so it left them relative agency to exert their profession within and outside the margins of the art system: 207 of them exhibited at Salons held between 1791 and 1815. A few years after the opening the National School of Fine Arts however, they were completely excluded from academic training. As Vigée-Lebrun prophesised: “women reigned supreme. The Revolution overthrew them”.

gender and artistic genres

Because they were restricted to the production of pictorial genres deemed as less “noble” and barred access to certain institutions, women have been written off art history. Besides, most recent publications have turned their attention onto artists from the mid-19th century onwards. Because of lost, detroyed or misattributed works, there’s been no thorough upkeep of women’s stories preceding this period. Some birthdates from the French classical period are still open to debate, as is the case with Louise Moillon (1609/10-1696). Quite exemplary in the decrease of her production after marriage to dwell into household duties, she was mainly active around 1630-1640. Entering the artistic vocabulary around this time, “still-life” didn’t require huge studio space or extensive anatomical knowledge.

Oil on canvas, 48 x 65 cm

It was thought that because of their “weaker” nature, women were incapable of creating or becoming geniuses. In the studio, they prepared canvasses for their master, worked on secondary elements of the composition and copied from those for training. As the Academy’s foundation corresponded to the liberal conception of fine arts, female practice was often associated to crafts. On moral grounds, respectable ladies were forbidden to attend life classes and draw from the nude, thus resorting to a more limited range of formats and techniques.

The controversy launched by the priest of Fontenay in the Journal General de France was exemplary: he argued that representing the nude damaged female decency. Since artists and especially Academicians had to forge their identity around respectability, this was problematic for women trying their hands at the “Grand Genre”, that is, history painting requiring mastery of the human figure through anatomy. 2 years before, the reception piece of Vigée-Lebrun provoked scathing reviews for its lack of idealisation and bare breast exposure. The painter had revealed that despite her lack of academic training in the nude, she could rival with her male counterparts in her rendering of sensuous flesh inspired by her study of Rubens in the Louvre collections.

Oil on canvas, 103 x 133 cm

“Pretty”, “nice”, “delicate”, “sensitive”, “gentle”, “discreet”: a whole new lexicon developed around female creation, believed to spring directly from their inner nature. At times, critics were questioning the authorship of artworks made by women. Despite her efforts to call him “M. Prudh’on” in public, Constance Mayer (1775-1821) suffered from constant associations to her master and lover. Identification of some works is complexified by facts that the couple often worked on the same canvasses, but unsigned paintings of hers have almost always been attributed to her partner. While he produced the preliminary sketch for The Dream of Happiness, Mayer altered the composition by removing the cherubs and giving the human figures more finish.

Oil on canvas, 132 x 184 cm

Some, on the other hand, entirely gave up subject-matters for which they received criticism. Anne Vallayer-Coster discarded portraiture from 1791, while her still-lives were said to be “manly”. She attempted to enoble the genre by achieving a great level of likeliness. Her participation at the Salon of 1771 caused philosopher Diderot to exclaim: “if all new members of the Academy made a showing like Mademoiselle Vallayer’s, and sustained the same high level of quality, the Salon would look very different. Mademoiselle Vallayer astonishes us, even as she delights us – here is Nature rendered with an inconceivable force of truth, and at the same time, a sense of colour that is seductive. Everything is well-observed and felt.”

1769, oil on canvas, 130 x 97 cm

Collections’ updates

Since 2014, there has been several attempts to make women artists more visible in the Louvre, but these events have been limited to temporary enterprises. The symposium in partnership with the Art History National Institute was inspired by the writings of English-speaking feminist art historians who had a decisive impact on research about female creation. It analysed the role of gender studies in art history, focussing on figures like Judith or examining the importance of fashion in the paintings of Nissa Villiers (1774-1821). 2 years later, a series of lectures labelled “Artists in the Classical Age” dealed with the conditions of practice by women painters. Sadly, by jumping from “stars” to lesser-known figures and priviledging biographical material, there was no reflection on gender categories, no overview nor contextualisation. Eventually, the Louvre has been interestingly active on social media in 2017, when the Museum Week (the first online event on Twitter) promoted #womenMW, probably in echo to the surge of interest in women’s stories provoked by the #MeToo movement.

Oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm

Without easily accessible data to look for these artists, it is essential to cross information in order to obtain a satisfying result. Many pieces are recorded on the drawings and prints – media rarely displayed due to their frailty – database of the Louvre. Unfortunately, these resources haven’t entirely been translated yet. To this date, about 700 works have been found, by some 30 artists or so, most of them kept in storage. From auction at Sotheby’s in December 2019, the Louvre acquired a canvas by Marguerite Gérard, the pupil then close associate to Jean-Honoré Fragonard. The Interesting Student is one of the first pictures signed by her hand.

Marguerite Gérard, The Interesting Student, 1768

Oil on canvas, 65 x 49 cm

Marie-Anne Collot, Unidentified Portrait, 1765

Terracotta, 40 x 54 x 25 cm

To my knowledge, there are only two female sculptors in the collection. Marie-Anne Collot (1748-1821), who operated in the studio of Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne, made this bust little before her departure to Russia. Félicie de Fauveau (1801-1886) was involved in the Gothic revival. The Lamp of St Michael of 1830 features the patron of chivalry surrounded by his squires. The Louvre also features works by foreign artists. Thanks to its social mobility, its senators supporting the arts and equal educational opportunities, many women painters were active in Bologna. Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614), who had a doctorate, wrestled directly with her male competitors on the art market, supporting her husband and 11 children.

Graphite, brown ink and gray wash on paper, 23x 16,3 cm

When you visit the Louvre, it requires a lot of time and attention to locate women artists on display. If you’re patient enough to make your way to the Flemish galleries, you’ll have the pleasure to admire The Jolly Couple by Judith Leyster (1609-1660), formely attributed to her rival Frans Hals. The discovery of a star inscribed near the signed monogram when the picture got to the Louvre in 1893 led experts to reassess it. This alluded to the painter’s family name and business; Leyster meaning pole star in Dutch was how her father had called his own brewery.

In addition to that, some works, visible a couple of years ago, are back in storage, lent or donated to other institutions. The Baronness of Krüdener by Anglo-Swiss Angelika Kauffmann (1740-1807) used to be displayed in the paintings section but the opening of the Louvre-Lens in 2012 revealed a need to de-centralise the initial collection. During her Grand Tour, Kauffmann stayed in Rome where she met with the ambassador of Russia’s wife. The simplicity of female grab – the Empire-styled dress of muslin – disclosed her knowledge of the latest European fashions.

Judith Leyster, Jolly Couple, 1630, oil on wood

57 x 68.5 cm

Angelika Kauffmann, The Baronness of Krüdener and her son Paul, 1786

Oil on canvas, 104 x 130 cm

Institutional and economic context from the Renaissance to the 1830s made it complex for women who were integrated and/ or rejected by the art system, dependent on successive governments and political upheavals. In that sense, the 19th century marked a step back after the possibilities opened by late 18th century careers and the potentials of the Revolution. Though an example for museums in Europe and abroad, the Louvre established itself around gender difference. Women’s legacies entering the museum are thus valuable assets to shatter traditional art histories and create alternative narratives. We also need to remember that female creation didn’t start in the 19th century and that previous women artists other than Vigée-Lebrun, if curbed by tradition, popular belief or politics, were numerous and effective onto the art scene.

Fancy booking a tour of the Louvre? You’ll find all details of your visit here: womensarttours.com/visite/the-real-queens-of-the-louvre/.