Painter from the Dutch Golden Age, Judith Leyster excelled at scenes of daily life, served by loose brushwork and dramatic contrasts in light and shade

a star is born

Eighth child out of 9 siblings, Judith Leyster grew up in Haarlem, Netherlands. Her surname was “Ley Ster”, translating as “pole star”. The family moved to the region of Utrecht at the end of the 1620s. As opposed to many of her female contemporaries Judith Leyster didn’t come from an artistic background. In fact she might have entered such a career to support her father from bankrupcy.

The Proposition, 1631

Oil on panel, 31 x 24 cm

Mauritshuis, The Hague

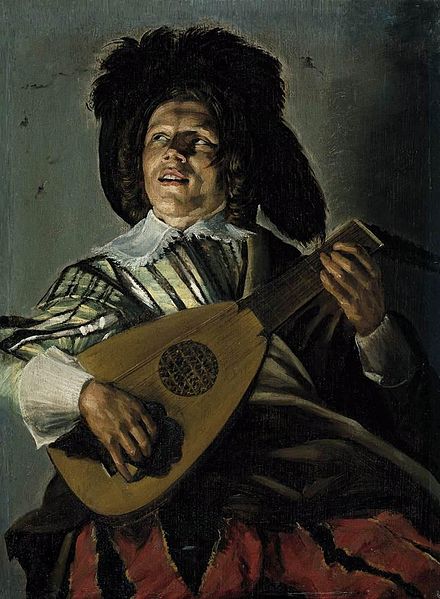

The Serenade, 1629

Oil on panel, 45.5 x 35 cm

Rijkmuseum, Amsterdam

Judith Leyster got accquainted with painters versed in the style of Caravaggio. This shows in her treatment of chiaroscuro, as in The Proposition. The woman doesn’t pay attention to the money the man offers her or his attempts at seduction, prefering to be entirely absorbed in her sewing. She’s lit full-face, and this effect is heightened by her white blouse. The male character looming over her, however, is characterised by darker hues, his shadow projected on the wall appearing as ominous. This intriguing picture differs largely from bawdy representations of daily life or people in merriment. Judith Leyster distorted title and subject-matter traditionally attributed to a sexually-charged encounter.

Great master

The details of Leyster’s education are uncomplete; she may have studied under history painter Frans Pietersz de Grebber or Frans Hals. Anyhow, she’s well-enough famous to be mentioned in 1628 by Dutch writer Samuel Ampzing. The first work by her hand was made in 1629.

Back in Haarlem, she made a self-portrait in order to increase her publicity, sitting in a dynamic yet relaxed pose to convey spontaneouness. She’s facing the viewer, mouth half-open as if to speak to him and entreat him to enter the studio. Leyster highlights her wealth and elegance by making a display of various fabrics, such as her lace collar (quite unconvenient for painting in truth!).

We have the impression to surprise her at work. She depicts herself with traditional tools, at her easel, brushes in hand, while the canvas in the making is not over yet. It features a variation of one of her favourite themes, Merry Company, made one year earlier. She then established a link between the visual arts and those of musical harmony.

Self-Portrait, 1630

Oil on canvas, 74.6 x 65.1 cm

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Merry Company, 1629-1631

Oil on canvas, 88 x 73.5 cm

Private collection

In 1633, Leyster was admitted at the Guild of St Luke, receving the title of Master Painter. This allowed her to teach and get some apprentices in the studio. Her acceptance as first woman artist to the corporation is subject to debate today. The Guild might have had several female members before, but within the domain of crafts or as male painters’ collaborators.

Painters had had the liberal status of their practice certified since the 16th century in the Netherlands, ranking on the same level as literature or mathematics, to become independent from manual trades. Anyway, no woman was granted membership by the Guild after Leyster, for the rest of the century.

What’s in a name?

A few years after starting teaching, Leyster had to sue her rival Frans Hals for accepting in his workshop one of her students who had left hers 3 days before. The Guild’s archive have recorded that the apprentice had been compelled to pay the sum of 4 florins to Leyster, that is, half of what she demanded. Frans Hals settled the matter by keeping the pupil and paying Leyster 3 extra florins. In the end, the Guild required another fine from Lesyter for not having recorded the apprentice as hers.

Leyster’s technique is closer to Dirk Hals (Frans’ brother), but these connections contributed to her work’s misattributions. Besides, she married painter Jan Miense Moelnaer in 1636, cutting short her independent professional career. Leyster assisted her husband in his artistic production, but she mainly took care of household duties and their 5 childen. She fell ill in 1659 and died the following year. The majority of her pictures were donated or sold to other painters.

Flute Player, 1635

Oil on canvas, 73 x 62 cm

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Flowers in a vase, 1654

Oil on panel, 50.4 x 69.7 cm

Private collection

Belated recognition

The discovery of her initials or her five-pointed star monogram on some canvasses at the end of the 19th century enabled scholars to re-instate the authorship of her oeuvre. We know about 35 paintings by her. Mainly a genre artist and a portraitist, she also made a history painting drawn from the Old Testament, David with the Head of Goliath (1633).

Very few pieces after her marriage remain: two illustrations in a flowers manual of 1643, a portrait of 1652, and a still-life executed in 1654, recently recorded in a private collection. Her last artwork was made in watercolour and silverpoint on vellum paper.

Judith Leyster has lately been celebrated in Washington museums, on the National Gallery’s website (www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1485.html#works) or at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, that dedicated an exhibition in 2019 to Flemish women artists: nmwa.org/art/artists/judith-leyster/.

61 x 86.7 cm, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington

How about talking about Judith Leyster in location, face-to-face ? She features on the Louvre tour, on the 2nd floor of wing Richelieu: womensarttours.com/visite/the-real-queens-of-the-louvre/